|

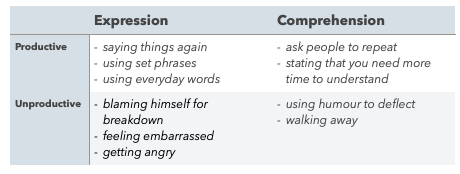

THIS POST WAS WRITTEN SOME WHILE AGO. THE BLOG REFERENCES SOME TRAINING I. ATTENDED CIRCA. 2015 BUT THE PRINCIPLES EXTEND BACK YEARS (NOTE INFLUENCE OF YLVISAKER) AND HAVE ENDURING RELEVANCE FOR OUR WORK NOW AND INTO THE FUTURE! Having listened to Jacinta Douglas present the evidence for the Communication Specific Coping Strategies Intervention (CommCope-I), I turned to my colleague and said ‘I must try this with Stephen!’. Using the La Trobe Communication Questionnaire (LCQ), we had recently identified cognitive communication difficulties that were barriers to Stephen’s social communication, including poor eye contact and turn-taking, distractibility and reduced memory. I felt that CommCope-I provided a methodical approach for identifying and practicing strategies that helped to overcome these barriers through graded and meaningful scenarios. A little about Stephen .... Stephen sustained a TBI during a competitive sporting event. He is married with a young family and ran a successful business. He had always been the ‘life and soul’ of social occasions. Following the accident, Stephen returned home with the support of his family and carer but often withdrew from family and social settings. Stephen wanted to re-establish roles in family life and improve the quality of his interactions with significant people at home and in the community. Using CommCope-I with Stephen Stage 1 - Facilitating Awareness Stephen found it difficult to learn and apply new strategies but his team already knew that he used some strategies naturally, i.e. responding to a code word to prompt him to slow down his speech. When used to repair breakdown in conversation, the CommCope-I calls this a communication-specific coping strategy (Douglas et.al, 2015). Studies have shown that communication-specific coping strategies account for better social outcomes (Friedman and Douglas, 2005) than improvements in communication ability alone (Snow et. al. 1998). Stephen, his wife and carer completed the Communication Specific Coping Scales (CommspeCS) questionnaire (Douglas & Mitchell, 2012) to identify Stephen’s existing strategies. The CommspeCS comprises two sets of forms, one for the client and one for close others. There are two sets of statements about strategies that can be used to address communication breakdown, 35 statements each for expression and comprehension, some productive and some non-productive. Using communication-specific coping strategies when communication breaks down is an experience common to us all. Difficulties arise for people with TBI when the pattern of strategies is weighted more towards non-productive (making communication more difficult) than productive strategies (making interactions easier) (Friedman & Douglas, 2005; Mitchell & Douglas, 2011; Muir & Douglas, 2007). The CommCope-I aims to accentuate the productive strategies. There was a consensus between Stephen, his wife and the carer around the following strategies: A key feature of CommCope-I is identifying six social scenarios to work on over twelve weeks. These scenarios were ranked according to Stephen’s perception of difficulty. Therapy began with the least challenging scenario. CommCope-I provided a workable structure but allowed the treatment to be flexible, shaped around Stephen’s unique needs. The conversation about potential scenarios ensured that we did not neglect important aspects of Stephen’s everyday life, including those at an apparently low level. For example, Stephen is friendly and missed welcoming people into his own home. Owing to his physical difficulties he found it challenging to open the front door, exchange greetings and stay standing whilst guests entered the home. This was successfully addressed in Scenario 1. Stage 2 - Develop skills CommCope-I draws on two established therapeutic principles firstly cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and secondly context-sensitive social communication therapy (Ylvisaker, 2006). CBT places emphasis on working with the client’s current communication behaviours and shaping them for different scenarios. One of Stephen’s productive strategies was using set phrases and he was able to apply this effectively to different scenarios. To ensure that Stephen embedded ‘set phrases’ across his everyday communication we drew on the second therapeutic principle of context-sensitive social communication therapy (Ylvisaker, 2006). We developed scripts that Stephen practiced in the session. The carer used the scripts in role play between sessions before Stephen employed the strategies in increasingly unstructured interactions. Stephen noticed that guests were naturally interested to find out about his recovery but that conversations quickly closed down if he answered questions about himself or if he did not feel like talking about himself. He wanted to shift the focus away from his own situation and establish more balanced interactions. He decided to respond to kind enquiries by saying “I’m fine thanks but more importantly how are you?”. This simple phrase opened up conversations because Stephen went on to ask follow up questions based on his communication partner’s answer which lead to a more satisfying interaction. Stephen wanted to help his children with their spellings but found it difficult to manage his own frustration if the children were uncooperative. We decided that it was helpful to (a) set the right tone, (b) praise and (c) offer reward. The script comprised three key phrases: S: Let’s do your spellings, it’s boring but everyone’s got to do it S: You’re so good at this set, let’s continue S: Let’s concentrate for 10 minutes then we can have a treat! Over time, Stephen supported spelling practice with the distant supervision of his carer. Helen, Stephen's carer, reflected on the value of the programme for their work together: We used set phrases effectively in daily interactions, which did much to keep communication positive and light between us: Stage 3 - Evaluate performance

The carer developed excellent candid camera skills (with Stephen’s permission) capturing social interactions as they unfolded. She also provided bi-weekly written feedback and together with self-rating from Stephen we were able to build a picture of growing confidence in social interactions. On CommspeCS, Stephen reported positive outcomes in his everyday interactions and the carer noted a more consistent use of productive strategies and a reduction in non-productive strategies e.g. walking away from difficult situations. References Douglas, JM; Knox, L; De Maio C and Bridge H Improving Communication-Specific Coping after Traumatic Brain Injury: Evaluation of a New Treatment using Single-case Experimental Design BRAIN IMPAIRMENT (2015) volume number pages Douglas, J and Mitchell, C. Measuring communication-specific coping: Development and evaluation of the Communication-specific Coping Scale. Brain Impairment, (2012) 13(1), 170–171. Friedman, A. & Douglas, J. Social participation and coping with communication breakdown following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, (2005). Supplement, 50–51. Mitchell, C., & Douglas, J. Coping with communication breakdown: A comparison between adults with severe TBI and healthy controls. Brain Impairment, (2011) Supplement, 41. Muir, A., & Douglas, J. Coping with communication breakdown after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment (2007) 8, 83. Snow, P., Douglas, J., & Ponsford, J. Conversational discourse abilities following severe traumatic brain injury: A longitudinal follow-up. Brain Injury (1998) 11, 911–935. Ylvisaker, M.Self-coaching: A context-sensitive, person-centred approach to social communication after TBI. Brain Impairment (2006) 7, 235–246.

0 Comments

There has been a buzz around MacDonald Model of Cognitive Communication Competence (MoCCC) since it was published in 2017. Sheila MacDonald explained how the model supports assessment and treatment for people with acquired brain injury (ABI) at the inaugural Cognitive Communication Difficulties (CCD) Symposium in 2018. Speech therapists cite the model as a ‘go-to’ reference for understanding CCD and allied health professionals in my teams also connect with the model. The model captures the breadth and complexity of impairments following ABI as well as the ways in which impairments limit participation in everyday life. It was developed from the evidence spanning the last 4 decades but also selective; only including factors that:

Assessment During referral and assessment, the MoCCC supports the gathering and assimilation of meaningful information from a new client and their team (family, professionals, friends and carers). By asking referrers to tick which behaviours they have observed on the Cognitive Communication Checklist for Acquired Brain Injury (CCCABI) also written by MacDonald (2015), I can identify subtle communication changes and map them onto the MoCCC. This information enables me to tailor my initial interview to understand more about these observations. At the same time the layout of the model ensures that I explore the breadth of issues pertaining to each case by prompting discussion about each domain, for example:

With referral information and feedback from the initial conversation, I annotate a copy of the model. Representing a client’s perspective in this way highlights domains and/or skills within each domain that are particularly problematic. This is a model of competence, so we also start to see areas of strength, which can be encouraging for the client when so much seems to have become more difficult. We identify which areas of ‘Communication Competence’ are priorities and which can be consider for future episodes of care. The MoCCC helps me to determine my rationale for including (a) formal assessments, (b) informal assessment and observation or (c) close work with professionals, as well as the timing for each assessment. The formal assessment tool kit available to SLTs working with CCDs is growing. However, front-loading an episode of care with a raft of formal assessments is often counterproductive for someone with an ABI. It can be most helpful to start by addressing the client’s expressed needs, for example, if a client reports that they take everything literally ‘The Awareness of Social Inference Test’ is indicated but ‘The Functional Assessment of Verbal Reasoning and Executive Skills’ might not be so useful, as wonderful as that assessment is! Formal assessments are administered strategically but I find that the MoCCC helps me to continuously assess my clients, especially in a team where there is a constant flow of new information to fit into the picture and work with. I routinely give out social observation sheets that allow team members and sometimes clients to report notable interactions, commenting on strengths, weaknesses, risks and support needs. Since most of the communication challenges occur outside of speech therapy sessions, this information is invaluable for detecting and analysing where the real difficulties lie. For clients, it means we can bring real life events back into the therapy room, discuss them with reference to the MoCCC and consider how to improve competence in any given situation before sharing this with the team and conversation partners or going out into the community to apply the strategies. Treatment Increasingly, I use the MoCCC to visualise the plan for the session. I invite clients to mark the model (using pens or annotation tools) to share their own insights and make sense of their personal experiences since the last session. The annotated images are saved and referred to over the course of the intervention, which allows us to review patterns that emerge and identify the key factors at the root of these patterns as well as charting progress over time. When the key factor is a communication skill, the intervention looks familiar. Often the root of the problem is found in another domain and requires close work with other professionals. In this situation referring to the MoCC helps a client to see how something they are working on in another discipline has a bearing on their communication. By way of example, a client had completed an assessment of reading comprehension that revealed good comprehension skills but some mild difficulties with increasing volume of text. The client continued to report reading difficulties and the habit of resorting to educated guesses when they could not understand the information. Fatigue exacerbated reading comprehension, leading to frustration and anxiety. The team physio explained how vestibular difficulties meant that the client was using their eyes so constantly and intensely to maintain balance that when they were reading (particularly on computers) the client did not have the extra capacity to scan the page so missed information. Reading skills improved when we addressed posture, seating, physical stability, equipment and when therapeutic lens’ were prescribed. Alongside therapy, the model can be useful for supporting conversation with family members as I help them to make sense of their experiences, to understand the rationale for strategies and encourage them to understand how their feedback is insightful, even when not focused on communication skills. As I mentioned earlier, the model outlines communication competence so it is grounding for carers and family members to start by exploring the impact of different skills on their own communication, e.g. fatigue, worries or perhaps a temporary lapse in memory. Starting from this point can lead, more quickly, to that eureka moment when the complexities of ABI start to be demystified and carers acknowledgement that their loved one needs support to communication. Negotiating with funders Advocating for and justifying funding for ongoing therapy has become a larger proportion of my work, especially when I am proposing interventions that do not directly relate to the original referral. For example, a recent initial referral identified impaired speech as the salient communication difficulty. Following the initial episode of SLT, the client made significant gains and was able to read aloud with very clear speech for some time. However, his spontaneous speech was still brief. This was all the more perplexing as it was clear that the client wanted to share lots of interesting topics. Having completed a full language assessment (no difficulties) and discussed the case with the OT, we identified memory and planning impairments as the main difficulties limiting the client’s ability to generate narrative and discourse. Even as speech had improved, the client had hit an expressive ceiling owing to these CCDs. With support from conversation partners, the client is now able to converse by using 5Ws & H to structure narrative or conversation, which has lead to much more fulfilling communication amongst the family. The funder was willing to support ongoing speech therapy in a new direction because the rationale was evidenced and explained using the MoCCC. It seems impossible to overstate the depth, breadth and complexity of changes that occur following ABI, not only for the individual with the injury but also for family members, friends and colleagues. As the model shows, there are so many variables that no single client is the same as the next. In post-acute rehabilitation, my clients are living at home, engaging in multiple relationships and seeking to re-establish work and leisure roles. There is a lot to consider on so many different levels; sometimes it feels overwhelming! Yet, the MoCCC has been for me a tool that reduces that sense of overwhelm and helps both to contain and expand my thinking. It is containing because I can organise and make sense of the information that comes from many different sources, information that rarely comes as norms and standard deviations but as real experiences, feelings and stories. The psychologists might call this a formulation, a process by which problems can be understood in a theoretical framework so that meaningful plans are made for therapy. This is where the model is expanding! By providing a firm foundation for understanding the issues at play, I am able to draw on evidence and my experience working with different aspects of communication. I can collaborate with the team and work creatively with each individual on their journey towards communication competence. I wanted to start by discussing the MoCCC because I hope that future posts will refer back to the model and expand some of these ideas, for example using Communication Coping Strategies Intervention to promote strengths-based strategies. In the spirit of this blog, please share your thoughts about how the MoCCC influences your practice. References: MacDonald, Sheila (2015) Cognitive Communication Checklist for Acquired Brain Injury (CCCABI) CCD Publishing; Guelph, Ontario, Canada, N1H 6J2 , www.ccdpublishing.com MacDonald, S (2017) Introducing the model of cognitive-communication competence: A model to guide evidence-based communication interventions after brain injury, Brain Injury, 31:13-14, 1760-1780, DOI: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1379613 Welcome to blog post number T W O !

As this blog develops, one of my hopes is hear the voices of my clients talking about their experiences of living with an acquired brain injury. What better opportunity to give voice than in brain injury awareness week 2020. I am really pleased to welcome Tom Holden as the first client contributor. He shares his experience of gaining employment when recovering from a brain injury. Tom was involved in a cycling accident in July 2017 but following rehabilitation was able to return to university to complete his studies. Tom has dysarthria and asked Communication Changes to provide therapy to improve speech intelligibility. We were able to work through a series of exercises from the good old DDK rates right through to preparing a brain injury awareness presentation that Tom will be able to deliver in a range of contexts. Over to Tom, I started my final year of university in September 2018 which is when companies release their graduate scheme application process. I did apply to a few but the most helpful thing I did was to make a list of the graduate schemes that I wanted to apply to the following September. Fast forward 12 months and I was ready to hit the ground running with my applications! The challenges I faced and how I negotiated them: A lot of companies include a one-way video interview in their selection process. I found this particularly challenging as you only get 30 seconds from the time that the question appears to when you have to start your recorded answer. This was a particular problem for me as during my time in hospital, we discovered that the introduction of time pressure had a resulted in my brain going into a meltdown and not being able to function. I negotiated this by researching common questions and preparing answers which I could adapt if required. This helped because instead of spending 30 seconds floundering for an answer, I already knew the rough answer I was going to give, and I could spend the time thinking about how I could adapt it. I also noticed that the computers audio distorted my speech and reduced the clarity of the words that I was saying. As the video interview only gives you a short amount of time to make an impression, I was worried that I wasn’t leaving a positive one! Therefore, I spent a lot of time practicing my answers in my own time into the computer’s video camera. This allowed me to listen back to it and identify any areas that I found problematic. A very useful tip that Mary gave me was to actively slow down when saying a pair of words that are commonly said together. My speech was only going to improve if I tirelessly practiced and corrected the things that I noticed were wrong! Recording my answers in this way was very beneficial. I think that it is vital to practice these in my day to day speech not just the therapy sessions. Practicing these video recordings also allowed me to see what I looked like on the screen and if there were any distractions in the background. It is well worth checking the lighting as this can drastically change your appearance. One of the schemes that I applied for was the Business Graduate Scheme at Williams Advanced Engineering. I was invited for an assessment day which included an interview in October. I was nervous as not only was I aware that my speech could occasionally lose clarity, but it was also my first ever face to face interview! I remembered the techniques that Mary had taught me in our therapy sessions and took a few deep breaths to avoid getting too flustered. Additional tips: The additional tips that I would give for anybody trying to improve their speech, whether it is for an interview or just in day to day life, would be to:

Initially I was struggling to produce certain sounds and pairs of letters but with lots of practice I managed to improve in these areas. Also, the more I practiced the more I became aware of words and phrases that tripped my speech up. Therefore, I could implement the techniques that I had learnt to improve my speech more naturally in day to day speech and in interviews. It is well worth practicing in front of other people and asking for their feedback! This improves your confidence on the day and helps you to project both your voice and your appearance. 2. Own the brain injury Initially I was worried about how the interviewer would react to learning that I had a brain injury. I was comfortable talking about my brain injury and portrayed it in such a way that it highlighted the positive aspects of my character. Focus, commitment and resilience are some of the key personality traits that the interviewer is looking for in potential candidates and there is no better example of this than in your battle back against a brain injury My journey: Throughout my recovery I kept the dream of regaining my independence at the forefront of my mind. I thought of every little improvement as a small step in the right direction and it is the accumulation of all these steps that result in the bigger improvements and you achieving your long-term goal! Tom Holden A huge thank you to Tom for sharing his story and the value of speech therapy in preparing for the interview process. For those who are wondering, Tom did get the job! He starts in September 2020 but in the meantime he is working on the frontline in a local supermarket. 2019 was, for me, a year to celebrate two significant milestones; two decades since qualifying as a speech and language therapist and one as an independent practitioner. It has been a time to reflect on the changes that unfolded, both in my practice and within the profession.

By way of illustration, I have a strong memory of delivering a presentation as an undergraduate during a module on acquired communications disorders. The topic was ‘subclinical aphasia’ as experienced following traumatic brain injury (TBI). This short label powerfully indicates how little was understood about communication difficulties following TBI back in the early 1990’s. We borrowed knowledge from the field of stroke and had a limited grasp on the myriad clinical features experienced by our clients. Fast forward to today and consider Sheila MacDonald’s 'Model of cognitive-communication competence’ which helps us to “[conceptualise] the full range of communication impairment after acquired brain injury“ (2017). This model draws together the many and varied clinical features involved in communication following TBI. This gives a theoretical background to what I see every day in practice - that the experience of cognitive communication difficulties is as unique as the individuals involved, influenced by their personal context as well as the injury. Coming back to my presentation all those years ago, it sticks in my mind because it was one of the earliest opportunities I had to explore the barriers that existed for people with TBI as they tried to re-engage with their life roles. As the profession has developed in its understanding and management of people with brain injury, so have I. I have been able to work at every stage of the pathway from ITU to post acute rehabilitation. I now spend my working days alongside people who are living with cognitive communication impairment, together with family, friends, and sometimes their colleagues, as they aim to re-engage with social, work and leisure roles in their own community. My goal is always to encourage and support my clients to live life to the full through the creative development of therapy programmes drawing on the evolving evidence base. Keeping up-to-date with research and other developments can be challenging enough but more so, working independently with less readily available spaces to share ideas with colleagues about application of theory in practice. Technology helps; Twitter is a fantastic window for discovering what colleagues are thinking about and doing in their work, almost in real time. Webinars provide remote access to more regular training and discussion with colleagues. Peer groups provide a safe space to have face to face discussions with trusted colleagues. The ever burgeoning body of blogs and vlogs allows speech therapists to share their ideas more widely, however, to date, I have not been able to find any fellow speech therapists blogging about their experience and practice in the area of cognitive communication following TBI. 2019’s milestones provided not only an opportunity for reflection but also the catalyst for seeking a new challenge. Having failed to discover anyone writing about the topic that interests me so much, I decided to become the answer to my own google search. In writing this blog, I hope to share some of my ideas about practicing as a speech and language therapist in the area of cognitive communication competence and invite conversation about how we as a profession can continue to address the needs of our clients creatively, especially as they return to family, leisure and work life. Where possible, I will give a space for my clients to ‘Give Voice’ by way of focusing on the most important people in this discussion and to provide hope for those who are starting out on their journey of recovery. Amongst the topics I hope to explore are ways to explain the complexities of cognitive communication competence to clients and their families (especially in relation to clinical assessments), new research into the role of the cerebellum (van Dun et.al. 2016) in social communication, the broadening view of Diffuse Axonal Injury (McDonald et al. 2019) and what all this might mean for my clients. I hope this piques your interest; please watch this space for blogs in the coming months and feel free to join the conversation using the comments box below. References Sheila MacDonald (2017) Introducing the model of cognitive-communication competence: A model to guide evidence-based communication interventions after brain injury, Brain Injury, 31:13-14, 1760-1780, DOI: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1379613 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed